PACE, the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly, adopted a Resolution on 24 January 2013 calling for “firm and urgent measures [to] tackle the mounting pressure and tension over asylum and irregular migration into Greece, Turkey and other Mediterranean countries.” The Resolution noted that Greece, with EU assistance, has enhanced border controls, particularly along its land border with Turkey and while “these policies have helped reduce considerably the flow of arrivals across the Evros border with Turkey, they have transferred the problem to the Greek islands and have not helped significantly in dealing with the situation of irregular migrants, asylum seekers and refugees already in Greece.”

The Resolution makes recommendations to the EU, Greece, and Turkey and calls on CoE members states to “substantially increase their assistance to Greece, Turkey and other front-line countries” in various ways, including:

- provide bi-lateral assistance, including by exploring new approaches to resettlement and intraEurope relocation of refugees and asylum seekers;

- share responsibility for Syrian refugees and asylum seekers via intra European Union relocation and refrain from sending these persons back to Syria or third countries;

- maintain a moratorium on returns to Greece of asylum seekers under the Dublin Regulation.

The Resolution was supported by a Report prepared by Ms Tineke Strik, Rapporteur, PACE Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced Persons.

Click here for full text of Resolution 1918(2013), Migration and asylum: mounting tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Click here for PACE press statement.

Click here for Report by Rapporteur, Ms Tineke Strik, Doc. 13106, 23 Jan 2013.

Here are extensive excerpts from the Rapporteur’s Report (which should be read in its entirety):

“Summary – Greece has become the main entry point for irregular migratory flows into the European Union, while Turkey has become the main country of transit. [***]

Europe must drastically rethink its approach to responsibility sharing to deal with what is a European problem and not one reserved to a single or only a few countries. Member States are called on to substantially increase their support for Greece, Turkey and other front-line countries to ensure that they have a realistic possibility of dealing with the challenges that they face. In this the Council of Europe also has a role to play, for example through exploring resettlement and readmission possibilities, assisting States in dealing with their asylum backlogs and putting forward innovative projects to alleviate growing racism and xenophobia towards migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

[***]

C. Explanatory memorandum by Ms Strik, rapporteur

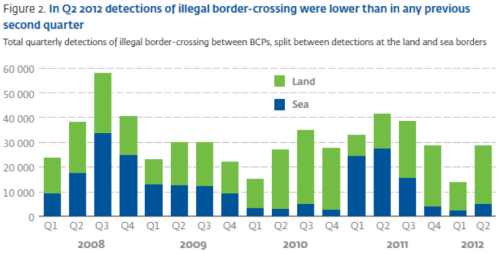

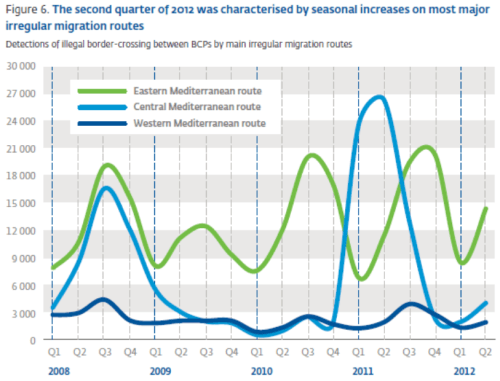

1. Introduction

[***]

2. Greece is facing a major challenge to cope with both the large influx of mixed migratory flows, including irregular migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, and the current economic crisis. That said it is not the only country struggling to cope in the region. It is impossible to look at the situation of Greece without also examining that of Turkey, which is the main country of transit to Greece and is also having to shoulder responsibility for over 150 000 Syrian refugees.

3. In the light of the foregoing, it is necessary to examine the extent of the migration and asylum challenges at Europe’s south-eastern border, taking into account Turkey and Greece’s policy reactions. Two further elements have to be added to this, namely the social tensions arising within Greek society due to an overload of financial and migratory pressure and also the issue of shared responsibility in Europe for dealing with European as opposed to simply national problems.

2. The storm at Europe’s south-eastern border

2.1. Greece under pressure: irregular migration challenge and economic crisis

4. In recent years, hundreds of thousands of irregular migrants, asylum seekers and refugees crossed the Greek land, river and sea borders with many travelling through Turkey. In 2010, the large majority of mixed migratory flows entered the European Union through the Greek-Turkish border. This situation brings major challenges in terms of human rights and migration management.

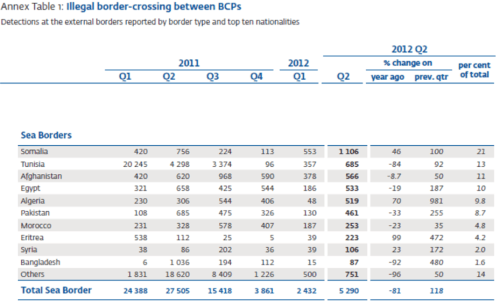

5. According to statistics provided by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in 2010, more than 132 000 third-country nationals were arrested in Greece, including 53 000 in the Greek-Turkish border regions. During the first ten months of 2012, over 70 000 arrests occurred, including about 32 000 at the borders of Turkey. People came from 110 different countries – the majority from Asia, including Afghanis, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, as well as from Iraq, Somalia, and the Middle-East, especially Palestinians and an increasing number of Syrians.

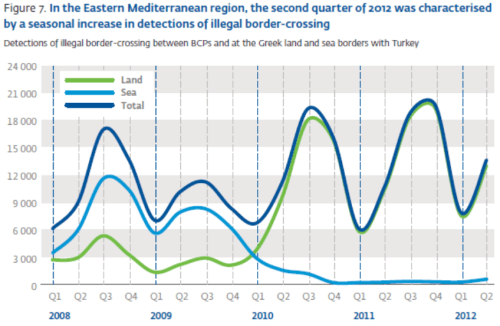

6. Most migrants and asylum seekers do not want to stay in Greece and plan to continue their journey further into Europe. Many of them are however stuck in Greece, due to border checks and arrests when trying to exit Greece, the current Dublin Regulation, and the fact that many irregular migrants cannot be returned to their country of origin.

7. The context of the serious economic and sovereign debt crisis aggravates the situation and reduces the ability for the Greek Government to adequately respond to the large influx. [***]

2.2. Syria: a bad situation could get worse

8. In its Resolution 1902 (2012) on “The European response to the humanitarian crisis in Syria”, the Parliamentary Assembly condemned “the continuing, systematic and gross human rights violations, amounting to crimes against humanity, committed in Syria”. It described the humanitarian situation as becoming “more and more critical” for the estimated 1.2 million internally displaced Syrians and the 638 000 Syrians registered or awaiting registration as refugees in neighbouring countries.

[***]

11. By October 2012, 23 500 Syrian nationals had applied for asylum in EU member States, including almost 3 000 applications in September 2012 alone, and over 15 000 in Germany and Sweden. Compared to neighbouring countries, asylum seeker numbers in the European Union currently remains manageable. However the number of Syrians trying to enter Greek territory in an irregular manner reached a critical level in July 2012, when up to 800 Syrians were crossing the Greek-Turkish land border every week. In the second half of 2012, more than 32% of sea arrivals to the Greek Islands were Syrian nationals.

2.3. Regional implications of mixed migratory arrivals

12. In recent years, Spain, Italy and Malta were at the forefront of large-scale sea arrivals. According to the UNHCR, in 2012, 1 567 individuals arrived in Malta by sea. 75% of these persons were from Somalia. The UNHCR estimates however that less than 30% of the more than 16 000 individuals who have arrived in Malta since 2002 remain in Malta.

13. Spain and Italy have signed and effectively enforced readmission agreements with North and West African countries cutting down on the mixed migration flows. These agreements have provided the basis for returning irregular migrants and preventing their crossing through increased maritime patrols and border surveillance, including in the context of joint Frontex operations.

14. As a consequence of shifting routes, migratory pressure at the Greek-Turkish border increased significantly and Greece became the main gate of entry into the European Union from 2008 onwards, with an interval in 2011 when the Arab Spring brought a new migratory flow to Italy and Malta. To give an idea of how much the routes have changed, Frontex indicated that in 2012, 56% of detections of irregular entry into the European Union occurred on the Greek-Turkish border.

15. Turkey, by contrast, has become the main transit country for migrants seeking to enter the European Union. Its 11 000-km-long border and its extensive visa-free regime make it an easy country to enter. An estimated half a million documented and undocumented migrants currently live in the country. This has brought a whole new range of challenges for Turkey and meant that it has had to develop a new approach to migration management and protection for those seeking asylum and international protection. It has also faced problems in terms of detention of irregular migrants and asylum seekers. As with Greece, the conditions of detention have been highly criticised and steps are being taken to build new centres with the assistance of funding from the European Union.

16. Until recently, the traditionally complex Greek-Turkish political relations did not allow the pursuit and consolidation of an effective readmission policy with Turkey. Although Greece, for example, signed a readmission protocol with Turkey which goes back to 2001, the implementation of this was only agreed on in 2010. It is important that this bilateral agreement between Greece and Turkey functions effectively and this will be a challenge for both countries.

3. Shielding Greece through border management and detention: does it work?

3.1. Enhanced border controls at the Greek-Turkish land border (Evros region)

17. The unprecedented numbers of irregular migrants and asylum seekers attempting to cross the Greek-Turkish border in recent years put the existing capacities and resources of Greece under severe strain. To remedy this situation, the Greek authorities have adopted the “Greek Action Plan on Asylum and Migration Management”, which is the basis for reforming the asylum and migration management framework in Greece.

18. In this context, considerable efforts were undertaken to reinforce Greece’s external borders and particularly the Greek-Turkish border in the Evros region. This was done notably through building up operational centres, using electronic surveillance and night vision devices, and by deploying patrol boats to strengthen river patrols. The surveillance technology used is part of the efforts under the European Border Surveillance System (Eurosur).

19. The so-called operation “Aspida” (“shield”), initiated in August 2012, aims to enhance border controls, surveillance and patrolling activities at the Greek-Turkish land border. Approximately 1 800 additional police officers from across Greece were deployed as border guards to the Evros region.

20. Increased border controls in the context of this operation have not been without criticism. There have been worrying reports about migrants, including refugees and asylum seekers from Syria and other countries, being pushed back to Turkey over the Evros river. Two incidents reportedly took place in June and October 2012, when inflatable boats were intercepted in the middle of the Evros river by Greek patrol boats and pushed back to Turkey before their boat was sunk, leaving people to swim to the Turkish shore.

21. In addition, the Greek authorities completed a barbed wire fence at the 12.5-km-land border in December 2012. The barrier which was criticised by EU officials when announced and built without EU funding, cost an estimated 3 million euros.

22. As a consequence of these actions, the numbers of irregular land border crossings dropped from over 2 000 a week in the first week of August to below 30 a week in the second half of September. According to the regional governor of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, they are now close to zero. While the Greek authorities claim that these actions have resulted in a more than 80% decrease of irregular entries, one can observe that migrants’ routes have shifted from the Greek-Turkish land border mainly to the sea border between both countries. This shift has been recognised by the Greek authorities.

23. Increased numbers of migrants are now arriving on the Greek Aegean islands of Lesvos, Samos, Symi and Farmkonissi. Between August and December 2012, 3 280 persons were arrested after crossing the Greek-Turkish sea border, compared to 65 persons in the first seven months of 2012.

24. There has also been an increase in the number of deaths at sea. In early September 2012, 60 people perished when their boat sank off the coast in Izmir. On 15 December 2012, at least 18 migrants drowned off the coast of Lesvos while attempting to reach the island by boat.

25. The spill over effect of new routes opening are now being felt by neighbouring countries, such as Bulgaria and some of the Western Balkans.

3.2. Systematic detention of irregular migrants and asylum seekers

26. Together with increased border controls, administrative detention remains the predominant policy response by the Greek authorities to the entry and stay of irregular migrants. [***]

[***]

29. Particularly worrying are the conditions in the various detention centres and police stations where irregular migrants and asylum seekers are held, and which have frequently been criticised. The European Court of Human Rights has found Greece to be in violation of the right to freedom from inhuman or degrading treatment in several cases in recent years. In addition, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment and Punishment (CPT) has regularly criticised the poor detention conditions of irregular migrants and asylum seekers and the structural deficiencies in Greece’s detention policy as well as the government’s persistent lack of action to improve the situation. See also: CPT, Report on its visit from 19 to 27 January 2011, published on 10 January 2012, at: www.cpt.coe.int/documents/grc/2012-01-inf-eng.pdf, together with the reply by the Greek authorities, at: www.cpt.coe.int/documents/grc/2012-02-inf-eng.pdf. The conditions of detention in one centre in Greece were found to be so bad that a local court in Igoumenista acquitted, earlier this year, migrants who were charged with escaping from detention stating that the conditions in the centre were not in compliance with the migrants’ human rights.

[***]

3.3. Impediments in accessing asylum and international protection

35. Despite the current efforts by the Greek authorities to reform the asylum and migration management framework, the country still does not have a fair and effective asylum system in place. The Greek Action Plan on Migration and Asylum, which was revised in December 2012, sets out the strategy of the Greek Government. It foresees the speedy creation of a functioning new Asylum Service, a new First Reception Service and a new Appeals Authority, staffed by civil servants under the Ministry of Public Order and Citizens Protection, disengaging the asylum procedure from the police authorities. However problems in finding sufficient financial resources and qualified staff still give rise for concerns on the implementation of the plans.

[***]

4. Social tensions within Greek society

4.1. The social situation of migrants and asylum seekers

41. Greece’s efforts to deal with the influx of irregular migrants and asylum seekers suffers from there being no comprehensive migration policy. [***]

4.2. Discrimination, xenophobia and racist attacks against migrants

46. The mounting social tensions and the inadequate response by the State to address the difficult social situation of migrants, asylum seekers and refugees have led to an increase in criminality and exploitation of this group. In addition, migration has become a key confrontational political issue. This in turn has contributed to an increasingly wide-spread anti-immigrant sentiment among the Greek population.

47. Over the last two years there has been a dramatic increase in xenophobic violence and racially motivated attacks against migrants in Greece, including physical attacks, such as beatings and stabbings, attacks on immigrants’ residences, places of worship, migrants’ shops or community centres. The Network for Recording Incidents of Racist Violence documented 87 racist incidents against migrants and refugees between January and September 2012. Half of them were connected with extremist groups.

48. Members and supporters of Golden Dawn have often been linked with recent violent attacks and raids against migrants and asylum seekers. By using blatantly anti-migrant and racist discourse, often inciting violence, Golden Dawn gained 7% of the popular vote during the June 2012 parliamentary elections and support seems to be growing, according to recent polls. In October 2012, the Greek Parliament lifted the immunity from prosecution of the two Golden Dawn MPs who participated in the violent attacks against migrants in September.

49. The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights has called on Greece to examine whether the “most overt extremist and Nazi party in Europe” is legal. It seems that Golden Dawn aims at political and societal destabilisation and gains by the failing policy regarding refugees and irregular migrants. In December 2012, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) expressed its “deep concern” about the rise of Golden Dawn and asked the Greek authorities to “take firm and effective action to ensure that the activities of Golden Dawn do not violate the free and democratic political order or the rights of any individuals”.

5. The European responsibility for a European problem

5.1. European front-line States under particular pressure

50. This is not the first time that the Parliamentary Assembly expresses its concern on the particular pressure that European front-line States are confronted with. Resolution 1521 (2006) on the mass arrival of irregular migrants on Europe’s Southern shores, Resolution 1637 (2008) on Europe’s “boat people”: mixed migration flows by sea into southern Europe and Resolution 1805 (2011) on the large-scale arrival of irregular migrants, asylum seekers and refugees on Europe’s southern shores.

51. Despite the fact that most European Union countries have stopped returning asylum seekers to Greece under the Dublin Regulation following the judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in the case M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, there are still some reports of returns from some countries based on this regulation.

52. The final agreement between the Council and the European Parliament on the revision of the Dublin Regulation still allocates responsibilities for asylum seekers to a single EU member State and does not present a more fundamental reform of the rules. European Union member States also rejected the idea of a mechanism to suspend transfers to those EU countries which were unable to manage the influx of asylum seekers into their territory, preferring to adopt an “early warning mechanism”.

5.2. Greece: A test case for European solidarity

53. This migratory pressure Greece is confronted with comes at a moment when the country is suffering as no other European country does from the current economic and social crisis. In response to these difficulties, the European Union has provided financial and technical assistance.

54. During the period of 2011-2013, Greece received 98,6 million euros under the Return Fund, 132,8 million euros under the External Border Fund and 19,95 million euros under the European Refugee Fund. The focus of funding was thus on border control and detention measures, to the detriment of the protection measures.

55. Frontex Joint Operation “Poseidon Land” was launched in 2010 at the borders between Turkey and Greece and between Turkey and Bulgaria. EU member States currently have 41 police officers and equipment deployed to the Evros border region in Greece. They also support the Greek and Bulgarian authorities with the screening and debriefing of irregular migrants, and tackling irregular migratory inflows and smuggling networks towards Greece. In addition, Frontex has recently strengthened its patrols in the coastal waters in the Eastern Aegean between Greece and Turkey in the context of Joint Operation “Poseidon Sea”. European Union member States have deployed additional maritime surveillance assets at the sea border between Greece and Turkey. The joint operation was extended to also cover the West coast of Greece and today is Frontex’s main operational activity in the Mediterranean region.

56. Furthermore, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) provides technical support to Greece and other EU member States whose asylum and reception systems are under particular pressure. Following the request by the Greek Government in February 2011, EASO started giving assistance and training in building up a new asylum system, improving reception conditions of asylum seekers in Greece and clearing the backlog of outstanding asylum claims. To do this they have deployed over 40 Asylum Support Teams of experts to the country.

57. While EU member States are ready to provide financial and technical assistance to help Greece in managing and controlling its borders, with a focus on both forced and voluntary returns as a policy solution, they are not keen on sharing the reception and processing of mixed migratory flows arriving at the European Union’s external border. According to the Greens/European Free Alliance of the European Parliament, “[m]igration will not be stopped by reinforcing border control, border management measures and forced returns; the current approach only reinforces human rights violations”.

58. As rapporteur I would largely agree with this statement, although I would add that while such policies may be able to solve a problem in one country, it then simply “passes the buck” to another. Should it be possible to seal Greece’s border, this would undoubtedly then put even greater pressure on Turkey and Bulgaria and then up the eastern borders of the European Union. This is an issue which will be the subject of a separate report by the Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced Persons.

59. The European Union response to the economic and financial crisis in Greece has been a massive bail out. Similar solidarity is however necessary with regards to the current social and humanitarian crisis in the field of migration and asylum. Europe is however doing too little, too late. A shared asylum policy that takes into account that the migratory pressures are not the sole responsible of one or a few European States, but a European problem, is even more essential in a time when the region is facing major instability. This instability will only increase further if the up and coming Golden Dawn party succeeds in exploiting the immigrant issue. Europe cannot afford to look away.

60. Increased migratory flows to European front-line States requires a fundamental rethink on solidarity and responsibility sharing. This includes swift solutions that go beyond mere financial and technical assistance and show greater solidarity in receiving refugees and asylum seekers and developing resettlement, especially currently for Syrian refugees from the neighbouring countries of Syria, and intra-EU relocation programmes, in particular where children and families are concerned. Assembly Resolution 1820 (2011) on asylum seekers and refugees: sharing responsibility in Europe provides meaningful recommendations in this respect.

6. Conclusions

61. The pressure of mixed migratory flows currently unfolding at the European Union’s external borders in the eastern Mediterranean requires rethinking of the entire solidarity system with the European Union and the Council of Europe. Greece, Turkey or other neighbouring countries should not be left with the primary responsibility of dealing with the mounting mixed migratory pressure from the South and East. A shared asylum and migration policy is even more essential at a time when the region is facing major economic and social instability.

62. Stricter border control, prolonging migrants’ and asylum seekers’ detention or constructing new detention facilities in Greece all contribute to further human rights violations taking place. They are not the way out of the problem and they do not persuade people fleeing from poverty or violence in their countries of origin to remain at home.

63. The recent efforts by the Greek authorities to introduce a more effective and humane system addressing the large number of irregular migrants and asylum seekers entering Greece is a welcome step in the right direction. Greece however faces a Herculean task in building up an efficient, fair and functioning system providing international protection to those in need.

64. Europe urgently needs to join forces to deal with the Syrian refugee problem, offering resettlement and relocation to relieve the burden falling on neighbouring States of Syria as well as its southern European States, and ensuring that Syrian refugees are not sent back.

65. The challenges are great but not insurmountable for Europe. Left to individual States they are.

[***]”

Click here for full text of Resolution 1918(2013), Migration and asylum: mounting tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Click here for PACE press statement.

Click here for Report by Rapporteur, Ms Tineke Strik, Doc. 13106, 23 Jan 2013.