Greek news reports say that Greek officials have made requests to Commissioner Malmström and Frontex for assistance to respond to “increasing migratory pressures on the islands of the Eastern Aegean.” The Greek islands of Lesvos, Samos, Patmos, Leros and Symi in particular have reportedly seen an increase in the number of persons entering from nearby Turkish territory. According to the media reports the assistance will include the deployment of “four aerial vehicle[s], four patrol boats, three mobile surveillance units and eight expert officers, whose costs will be covered by EU funds the agency and the European Commission.”

Tag Archives: Frontex

Frontex to Increase Sea and Air Patrols in Aegean at Greece’s Request

Filed under Aegean Sea, European Union, Frontex, Greece, Mediterranean, News, Turkey

HRW Briefing Paper: Hidden Emergency-Migrant deaths in the Mediterranean

Human Rights Watch released a briefing paper on 16 August entitled “Hidden Emergency-Migrant deaths in the Mediterranean.” The briefing paper, written by Judith Sunderland, a senior researcher with HRW, reviews recent events in the Mediterranean, provides updates on new developments, including the EUROSUR proposal and IMO guidelines that are under consideration, and makes recommendations for how deaths can be minimized.

Excerpts from the Briefing Paper:

“The death toll during the first six months of 2012 has reached at least 170. … Unless more is done, it is certain that more will die.

Europe has a responsibility to make sure that preventing deaths at sea is at the heart of a coordinated European-wide approach to boat migration, not a self-serving afterthought to policies focused on preventing arrivals or another maneuver by northern member states to shift the burden to southern member states like Italy and Malta.

With admirable candor, EU Commissioner Cecilia Malmström said recently that Europe had, in its reaction to the Arab Spring, ‘missed the opportunity to show the EU is ready to defend, to stand up, and to help.’ Immediate, concerted efforts to prevent deaths at sea must be part of rectifying what Malmström called Europe’s ‘historic mistake.’

Europe’s Response to Boat Migration

[***]

European countries most affected by boat migration—Italy, Malta, Greece and Spain—have saved many lives through rescue operations. But those governments and the European Union as a whole have focused far more effort on seeking to prevent boat migration, including in ways that violate rights. Cooperation agreements with countries of departure for joint maritime patrols, technical and financial assistance for border and immigration control, and expedited readmission of those who manage to set foot on European soil have become commonplace.

The EU’s border agency Frontex has become increasingly active through joint maritime operations, some of which have involved coordination with countries of departure outside the EU such as Senegal. Even though in September 2011 the EU gave Frontex an explicit duty to respect human rights in its operations and a role in supporting rescue at sea operations, these operations have as a primary objective to prevent boats from landing on EU member state territories. This has also prevented migrants, including asylum seekers, from availing themselves of procedural rights that apply within EU territory.

[***]

Italy had suspended its cooperation agreements with Libya in February 2011, and has indicated it will respect the European Court’s ruling and will no longer engage in push-backs. However, past experience suggests that an immigration cooperation agreement signed with the Libyan authorities in April 2012, the exact contents of which have neither been made public nor submitted to parliamentary scrutiny, is unlikely to give migrants’ human rights the attention and focus they need if those rights are to be properly protected.

[***]

Preventing Deaths in the Mediterranean

It may be tempting to blame lives lost at sea on unscrupulous smugglers, the weather, or simple, cruel fate. However, many deaths can and should be prevented. UNHCR’s recommendation during the Arab Spring to presume that all overcrowded migrant boats in the Mediterranean need rescue is a good place to start.

[***]

Recognizing the serious dimensions of the problem, specialized United Nations agencies such as the UNHCR and the International Maritime Organization (IMO), have been working to produce clear recommendations. These include establishing a model framework for cooperation in rescue at sea and standard operating procedures for shipmasters. The latter should include a definition of distress triggering the obligation to provide assistance that takes into account risk factors, such as overcrowding, poor conditions on board, and lack of necessary equipment or expertise. UNHCR has also proposed that countries with refugee resettlement programs set aside a quota for recognized refugees rescued at sea.

The IMO has also been pursuing since 2010 a regional agreement among Mediterranean European countries to improve rescue and disembarkation coordination, as well as burden-sharing. The project, if implemented successfully, would serve as a model for other regions. A draft text for a memorandum of understanding is under discussion. Negotiations should be fast-tracked with a view to implementation as quickly as possible.

If Europe is serious about saving lives at sea, it also needs to amend the draft legislation creating EUROSUR. This new coordinated surveillance system should spell out clearly the paramount duty to assist boat migrants at sea, and its implementation must be subject to rigorous and impartial monitoring. Arguments that such a focus would create a ‘pull factor’ and encourage more migrants to risk the crossing are spurious. History shows that people on the move, whether for economic or political reasons, are rarely deterred or encouraged by external factors.

[***]”

From the HRW press statement:

The “briefing paper includes concrete recommendations to improve rescue operations and save lives:

- Improve search and rescue coordination mechanisms among EU member states;

- Ensure that EUROSUR has clear guidelines on the paramount duty of rescue at sea and that its implementation is rigorously monitored;

- Clarify what constitutes a distress situation, to create a presumption in favor of rescue for overcrowded and ill-equipped boats;

- Resolve disputes about disembarkation points;

- Remove disincentives for commercial and private vessels to conduct rescues; and

- Increase burden-sharing among EU member states.”

Click here or here for HRW Briefing Paper.

Click here for HRW press statement.

Filed under European Union, Frontex, Italy, Libya, Malta, Mediterranean, Reports, Spain, Tunisia

400 Migrants Reach Lampedusa Over Past Weekend; Detention Centre Over Capacity; Former Interior Minister Maroni Calls for Resumption of Italy’s Push-Back Practice

Two large migrant boats reached Lampedusa over the past weekend. One of the boats was carrying about 250 persons, believed to be Sub-Saharan Africans, and is thought to have departed from Libya. The boat was a 15 meter wooden fishing vessel and appears to be one of the first non-inflatable boats used in many months. A second boat carrying about 125 Tunisians arrived around the same time. Smaller boats carrying mostly Tunisians have been steadily reaching Lampedusa in recent weeks. In response to the apparent increase in the numbers of persons reaching Lampedusa, former Italian Interior Minister Roberto Maroni (Northern League) wrote on his Facebook page and called for a resumption of Italy’s Push-Back practice to halt new boats. (“Tornano i barconi a Lampedusa. RESPINGIMENTI, come facevo io, questo serve per fermare l’invasione.”) Given the decision in the Hirsi case by the European Court of Human Rights, Italy is not likely to resume the push-back practice. 81 Sub-Saharan migrants on a disabled boat were rescued by Italian authorities on Monday. The detention centre on Lampedusa is over its 350 person capacity and Italian authorities have begun to transfer migrants to facilities elsewhere.

Filed under European Union, Frontex, Italy, Libya, Mediterranean, News, Tunisia

Malta Expresses Interest in Use of Drones for Migrant Surveillance at Sea

Malta Today reported last week that the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM) “have expressed interest in benefitting from a European Union-sponsored project involving the deployment of unmanned drones to assist in migrant patrols at sea.” “An AFM spokesman told Malta Today that while the armed forces are ‘fully involved in the development of the system’ it is however ‘not participating in the testing of such drones.’”

The use of drones for land and sea border surveillance is contemplated by the EU Commission’s EUROSUR proposal which is currently being considered by the European Parliament. The Heinrich Böll Foundation’s recent report, “Borderline – The EU’s new border surveillance initiatives”, noted that “[w]hile FRONTEX has demonstrated a great amount of interest in the use of drones, it remains to be seen whether the agency will purchase its own UAVs. According to the 2012 FRONTEX Work Programme, the agency’s Research and Development Unit is currently engaged in a nine-month study to ‘identify more cost efficient and operational effective solutions for aerial border surveillance in particular Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) with Optional Piloted Vehicles (OPV) that could be used in FRONTEX Joint Operations (sea and land).’”

The United States has been using drones for some years now to monitor land and sea borders and is currently planning to expand the use of drones in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico despite serious questions that are being raised about the effectiveness of surveillance drones operating over the sea. According to a recent Los Angeles Times article the Predator drones that are currently being operated by the Department of Homeland Security over the Caribbean “have had limited success spotting drug runners in the open ocean. The drones have largely failed to impress veteran military, Coast Guard and Drug Enforcement Agency officers charged with finding and boarding speedboats, fishing vessels and makeshift submarines ferrying tons of cocaine and marijuana to America’s coasts.” “‘I’m not sure just because it’s a UAV [unmanned aerial vehicle] that it will solve and fit in our problem set,’ the top military officer for the region, Air Force Gen. Douglas M. Fraser, said recently. … For the recent counter-narcotics flights over the Bahamas, border agents deployed a maritime variant of the Predator B called a Guardian with a SeaVue radar system that can scan large sections of open ocean. … But test flights for the Guardian [drone] showed disappointing results in the Bahamas, according to two law enforcement officials familiar with the program who were not authorized to speak publicly. During more than 1,260 hours in the air off the southeastern coast of Florida, the Guardian assisted in only a handful of large-scale busts, the officials said….”

Filed under European Union, Frontex, Malta, News

Slight Decrease in Number of Migrants Arriving by Boat in Spain in First Half of 2012

Frontex reports a 3% decrease in the number of irregular migrants arriving by boat in Spain over the first half of 2012 compared to the same period in 2011: 2,637 in 2011 versus 2,559 in 2012. Most migrant boats attempt to reach the Spanish mainland along the coasts of Andalusia and elsewhere in eastern Spain. Frontex reports an increase of 6.5% in the number of migrants reaching the Spanish mainland, but this increase is offset by a reduction in the number of migrant arrivals in the Canary Islands.

EFE quoted Gil Arias, Frontex deputy director, as stating that “[t]he decline [in Spain] is in line with the trend of the EU…” where there has been an overall reduction of more than 50% in the number of irregular migrants crossing land and sea borders of Member States during the same six month period: 74,200 in 2011 versus 36,741 in 2012. Arias noted that the number of arrivals in Spain is “insignificant” relative to the overall EU, accounting for about 7% of the EU total with Italy accounting for 12% and Greece 67%.

Note that there are other media reports which provide slightly different figures from those reported by Frontex. Europapress reported that an estimated 3,000 migrants have been rescued so far this year (apparently though late July) along the Andalusian coast by rescue services.

Filed under Algeria, Data / Stats, Eastern Atlantic, European Union, Frontex, Mauritania, Mediterranean, Morocco, News, Somalia, Spain

European Ombudsman Opens Public Consultation on Frontex and EU Charter of Fundamental Rights; NGOs and Public Invited to Submit Comments

Text of 19 July 2012 press release from the European Ombudsman: “The European Ombudsman, P. Nikiforos Diamandouros, has invited individuals, NGOs, and other organisations active in the area of fundamental rights protection to submit comments in his ongoing inquiry concerning the EU Borders Agency, Frontex. Frontex coordinates the operational cooperation between Member States in the field of border security. In March 2012, the Ombudsman asked Frontex a number of questions about the implementation of its fundamental rights obligations. Frontex replied in May 2012. Comments on Frontex’s response can be submitted to the Ombudsman until 30 September 2012.

Fundamental rights organisations and NGOs invited to submit comments

In 2009, the Charter of Fundamental Rights became legally binding on Frontex, which is based in Warsaw. Since then, a number of civil society organisations have questioned whether Frontex is doing enough to comply with the Charter, for example, in its deployment of EU border guards to Greece where migrant detainees were kept in detention centres under conditions which have been criticised by the European Court of Human Rights.

In October 2011, the European Parliament and the Council adopted a Regulation setting out additional specific fundamental rights obligations for Frontex. In March 2012, the Ombudsman asked Frontex a number of questions about how it is fulfilling these obligations, including the obligation to draw up a fundamental rights strategy, as well as codes of conduct applicable to its operations.

Frontex submitted its opinion in May 2012. It explained that, since 2010, it has developed a fundamental rights strategy, as well as a binding code of conduct for those participating in its activities. Frontex also listed other measures it is currently taking to ensure full respect for fundamental rights.

The Ombudsman considers that, before proceeding further, it would be useful to seek information and views from NGOs and other organisations active in the area of fundamental rights protection. He therefore invites interested parties to make observations on Frontex’s opinion. The Ombudsman has also invited the EU Fundamental Rights Agency to give its views.

All documents related to the inquiry, including Frontex’s opinion, are available at: http://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/cases/correspondence.faces/en/11757/html.bookmark ”

From the Ombudsman’s website:

What the Ombudsman is looking for

The present inquiry concerns the implementation by Frontex of its fundamental rights obligations. The Ombudsman would, therefore, be highly interested in receiving feedback from interested parties, such as NGOs and other organisations specialised in the areas covered by his inquiry, on Frontex’s answers to the questions he put to it.

The present inquiry is not intended to examine and solve individual cases involving Frontex’s fundamental rights obligations. Such cases can of course be submitted to the Ombudsman through individual complaints. A complaint form that can be used for this purpose is available on this website.

How to contribute

Comments should be sent to the Ombudsman by 30 September 2012.

- By letter: European Ombudsman, 1 avenue du Président Robert Schuman, CS 30403, F – 67001 Strasbourg Cedex, France;

- By fax: +33 (0)3 88 17 90 62;

- By e-mail: http://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/shortcuts/contacts.faces

Click here for press release.

Click here for all documents related to the inquiry.

Click here for Frontex’s 17 May 2012 response.

Filed under European Ombudsman, European Union, Frontex, News, Reports

Heinrich Böll Foundation Study: Borderline- The EU’s New Border Surveillance Initiatives, Assessing the Costs and Fundamental Rights Implications of EUROSUR and the ‘Smart Borders’ Proposals

The Heinrich Böll Foundation released a study written by Dr. Ben Hayes from Statewatch and Mathias Vermeulen (editor of The Lift- Legal Issues in the Fight Against Terrorism blog) entitled “Borderline – The EU’s new border surveillance initiatives: assessing the costs and fundamental rights implications of EUROSUR and the ‘Smart Borders’ Proposals.” The Study was presented to the European Parliament last month. As Mathias Vermeulen noted in an email distributing the study, “the European Parliament is currently negotiating the legislative proposal for Eurosur, and the European Commission is likely to present a legislative proposal on ‘smart borders’ in September/October.”

Excerpts from the Preface and Executive Summary of the Study:

“Preface

The upheavals in North Africa have lead to a short-term rise of refugees to Europe, yet, demonstrably, there has been no wave of refugees heading for Europe. By far most refugees have found shelter in neighbouring Arab countries. Nevertheless, in June 2011, the EU’s heads of state precipitately adopted EU Council Conclusions with far-reaching consequences, one that will result in new border policies ‘protecting’ the Union against migration. In addition to new rules and the re-introduction of border controls within the Schengen Area, the heads of state also insisted on upgrading the EU’s external borders using state-of-art surveillance technology, thus turning the EU into an electronic fortress.

The Conclusions passed by the representatives of EU governments aims to quickly put into place the European surveillance system EUROSUR. This is meant to enhance co-operation between Europe’s border control agencies and promote the surveillance of the EU’s external borders by FRONTEX, the Union’s agency for the protection of its external borders, using state-of-the-art surveillance technologies. To achieve this, there are even plans to deploy unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) over the Mediterranean and the coasts of North Africa. Such high-tech missions have the aim to spot and stop refugee vessels even before they reach Europe’s borders. A EUROSUR bill has been drafted and is presently being discussed in the European Council and in the European Parliament. [***]

EUROSUR and ‘smart borders’ represent the EU’s cynical response to the Arab Spring. Both are new forms of European border controls – new external border protection policies to shut down the influx of refugees and migrants (supplemented by internal controls within the Schengen Area); to achieve this, the home secretaries of some countries are even willing to accept an infringement of fundamental rights.

The present study by Ben Hayes and Mathias Vermeulen demonstrates that EUROSUR fosters EU policies that undermine the rights to asylum and protection. For some time, FRONTEX has been criticised for its ‘push back’ operations during which refugee vessels are being intercepted and escorted back to their ports of origin. In February 2012, the European Court of Human Rights condemned Italy for carrying out such operations, arguing that Italian border guards had returned all refugees found on an intercepted vessel back to Libya – including those with a right to asylum and international protection. As envisioned by EUROSUR, the surveillance of the Mediterranean using UAVs, satellites, and shipboard monitoring systems will make it much easier to spot such vessels. It is to be feared, that co-operation with third countries, especially in North Africa, as envisioned as part of EUROSUR, will lead to an increase of ‘push back’ operations.

Nevertheless, the EU’s announcement of EUROSUR sounds upbeat: The planned surveillance of the Mediterranean, we are being told, using UAVs, satellites, and shipboard monitoring systems, will aid in the rescue of refugees shipwrecked on the open seas. The present study reveals to what extent such statements cover up a lack of substance. Maritime rescue services are not part of EUROSUR and border guards do not share information with them, however vital this may be. Only just recently, the Council of Europe issued a report on the death of 63 migrants that starved and perished on an unseaworthy vessel, concluding that the key problem had not been to locate the vessel but ill-defined responsibilities within Europe. No one came to the aid of the refugees – and that in spite of the fact that the vessel’s position had been known. [***]

The EU’s new border control programmes not only represent a novel technological upgrade, they also show that the EU is unable to deal with migration and refugees. Of the 500,000 refugees fleeing the turmoil in North Africa, less than 5% ended up in Europe. Rather, the problem is that most refugees are concentrated in only a very few places. It is not that the EU is overtaxed by the problem; it is local structures on Lampedusa, in Greece’s Evros region, and on Malta that have to bear the brunt of the burden. This can hardly be resolved by labelling migration as a novel threat and using military surveillance technology to seal borders. For years, instead of receiving refugees, the German government along with other EU countries has blocked a review of the Dublin Regulation in the European Council. For the foreseeable future, refugees and migrants are to remain in the countries that are their first point of entry into the Union.

Within the EU, the hostile stance against migrants has reached levels that threaten the rescue of shipwrecked refugees. During FRONTEX operations, shipwrecked refugees will not be brought to the nearest port – although this is what international law stipulates – instead they will be landed in a port of the member country that is in charge of the operation. This reflects a ’nimby’ attitude – not in my backyard. This is precisely the reason for the lack of responsibility in European maritime rescue operations pointed out by the Council of Europe. As long as member states are unwilling to show more solidarity and greater humanity, EUROSUR will do nothing to change the status quo.

The way forward would be to introduce improved, Europe-wide standards for the granting of asylum. The relevant EU guidelines are presently under review, albeit with the proviso that the cost of new regulations may not exceed the cost of those in place – and that they may not cause a relative rise in the number of asylum requests. In a rather cynical move, the EU’s heads of government introduced this proviso in exactly the same resolution that calls for the rapid introduction of new surveillance measures costing billions. Correspondingly, the budget of the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) is small – only a ninth what goes towards FRONTEX.

Unable to tackle the root of the problem, the member states are upgrading the Union’s external borders. Such a highly parochial approach taken to a massive scale threatens some of the EU’s fundamental values – under the pretence that one’s own interests are at stake. Such an approach borders on the inhumane.

Berlin/Brussels, May 2012

Barbara Unmüßig

President Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung

Ska Keller

Member of the European Parliament

Executive Summary

The research paper ‘Borderline’ examines two new EU border surveillance initiatives: the creation of a European External Border Surveillance System (EUROSUR) and the creation of the so-called ‘smart borders package’…. EUROSUR promises increased surveillance of the EU’s sea and land borders using a vast array of new technologies, including drones (unmanned aerial vehicles), off-shore sensors, and satellite tracking systems. [***]

The EU’s 2008 proposals gained new momentum with the perceived ‘migration crisis’ that accompanied the ‘Arab Spring’ of 2011, which resulted in the arrival of thousands of Tunisians in France. These proposals are now entering a decisive phase. The European Parliament and the Council have just started negotiating the legislative proposal for the EUROSUR system, and within months the Commission is expected to issue formal proposals for the establishment of an [Entry-Exit System] and [Registered Traveller Programme]. [***]

The report is also critical of the decision-making process. Whereas the decision to establish comparable EU systems such as EUROPOL and FRONTEX were at least discussed in the European and national parliaments, and by civil society, in the case of EUROSUR – and to a lesser extent the smart borders initiative – this method has been substituted for a technocratic process that has allowed for the development of the system and substantial public expenditure to occur well in advance of the legislation now on the table. Following five years of technical development, the European Commission expects to adopt the legal framework and have the EUROSUR system up and running (albeit in beta form) in the same year (2013), presenting the European Parliament with an effective fait accomplit.

The EUROSUR system

The main purpose of EUROSUR is to improve the ‘situational awareness’ and reaction capability of the member states and FRONTEX to prevent irregular migration and cross-border crime at the EU’s external land and maritime borders. In practical terms, the proposed Regulation would extend the obligations on Schengen states to conducting comprehensive ‘24/7’ surveillance of land and sea borders designated as high-risk – in terms of unauthorised migration – and mandate FRONTEX to carry out surveillance of the open seas beyond EU territory and the coasts and ports of northern Africa. Increased situational awareness of the high seas should force EU member states to take adequate steps to locate and rescue persons in distress at sea in accordance with the international law of the sea. The Commission has repeatedly stressed EUROSUR’s future role in ‘protecting and saving lives of migrants’, but nowhere in the proposed Regulation and numerous assessments, studies, and R&D projects is it defined how exactly this will be done, nor are there any procedures laid out for what should be done with the ‘rescued’. In this context, and despite the humanitarian crisis in the Mediterranean among migrants and refugees bound for Europe, EUROSUR is more likely to be used alongside the long-standing European policy of preventing these people reaching EU territory (including so-called push back operations, where migrant boats are taken back to the state of departure) rather than as a genuine life-saving tool.

The EUROSUR system relies on a host of new surveillance technologies and the interlinking of 24 different national surveillance systems and coordination centers, bilaterally and through FRONTEX. Despite the high-tech claims, however, the planned EUROSUR system has not been subject to a proper technological risk assessment. The development of new technologies and the process of interlinking 24 different national surveillance systems and coordination centres – bilaterally and through FRONTEX – is both extremely complex and extremely costly, yet the only people who have been asked if they think it will work are FRONTEX and the companies selling the hardware and software. The European Commission estimates that EUROSUR will cost €338 million, but its methods do not stand up to scrutiny. Based on recent expenditure from the EU External Borders Fund, the framework research programme, and indicative budgets for the planned Internal Security Fund (which will support the implementation of the EU’s Internal Security Strategy from 2014–2020), it appears that EUROSUR could easily end up costing two or three times more: as much as €874 million. Without a cap on what can be spent attached to the draft EUROSUR or Internal Security Fund legislation, the European Parliament will be powerless to prevent any cost overruns. There is no single mechanism for financial accountability beyond the periodic reports submitted by the Commission and FRONTEX, and since the project is being funded from various EU budget lines, it is already very difficult to monitor what has actually been spent.

In its legislative proposal, the European Commission argues that EUROSUR will only process personal data on an ‘exceptional’ basis, with the result that minimal attention is being paid to privacy and data protection issues. The report argues that the use of drones and high-resolution cameras means that much more personal data is likely to be collected and processed than is being claimed. Detailed data protection safeguards are needed, particularly since EUROSUR will form in the future a part of the EU’s wider Common Information Sharing Environment (CISE), under which information may be shared with a whole range of third actors, including police agencies and defence forces. They also call for proper supervision of EUROSUR, with national data protection authorities checking the processing of personal data by the EUROSUR National Coordination Centres, and the processing of personal data by FRONTEX, subject to review by the European Data Protection Supervisor. EUROSUR also envisages the exchange of information with ‘neighbouring third countries’ on the basis of bilateral or multilateral agreements with member states, but the draft legislation expressly precludes such exchanges where third countries could use this information to identify persons or groups who are at risk of being subjected to torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, or other fundamental rights violations. The authors argue that it will be impossible to uphold this provision without the logging of all such data exchanges and the establishment of a proper supervisory system. [***]”

Filed under Analysis, European Union, Frontex, Mediterranean, Reports

1000+ Migrants / 44 Boats Reach Andalusian Coast in First Half of 2012; Frontex JOs Indalo and Minerva Underway

Europa Press reported that 1,037 migrants on board 44 boats have been detected arriving on the Andalusian coast from 1 January 2012 to 9 July 2012. Most of the arrivals have occurred in the provinces of Granada and Almeria. Frontex’s 2012 Joint Operation Indalo, which began in May , is focused on detecting irregular migration in the Western Mediterranean and specifically on migration from Morocco and Algeria towards Andalusia. The ABC newspaper reported that some Spanish officials are again concerned that the Frontex enforcement efforts will divert migrant boats further north along the coast of Alicante. The first boat of the year was detected arriving on the Alicante coast on 9 July. ABC reported that a source with the Guardia Civil predicted that the numbers of boats attempting to reach Alicante would be less this year due to the stabilizing of conditions in North Africa and the poor Spanish economy. Frontex’s Joint Operation Minerva will launch on 13 July and is focused on increased surveillance and inspection of passengers arriving in Spain by ferry from Morocco and arrivals in Ceuta.

Click here, here, here, and here for articles. (ES)

Click here and here for Frontex descriptions of 2011 JO Indalo and Minerva.

Filed under Algeria, Data / Stats, European Union, Frontex, Mediterranean, News, Spain

Boats4People Releases Mapping Platform to Monitor the Maritime Borders of the EU for Violations of Migrants’ Rights

Boats4People announced last week the release of a mapping platform to monitor “in almost real-time reported cases of migrants in distress at sea”. The project is called WatchTheMed and “is a collaboration between the Forensic Oceanography research project at Goldsmiths College and Boats4People, a campaign led by an international coalition of NGOs aiming at bringing an end to the death of migrants at sea and foster solidarity between both sides of the Mediterranean.”

Press Release: 03.07.2012 WatchTheMed

Boats4People Mapping Platform to Monitor the Maritime Borders of the EU for Violations of Migrants’ Rights

While Boats4People’s Oloferne boat is at sea, many other participants are contributing from the land in Italy, Tunisia, across Africa and Europe and even as far as the USA. Amongst them, researchers of the Forensic Oceanography research project at Goldsmiths, University of London, who, in the frame of the B4P campaign, have launched a new online mapping platform to monitor in almost real time the death of migrants and violations of their rights at the Maritime Borders of the EU.

Acting as a “civilian watchtower” over the Mediterranean, WatchTheMed aims to collect all possible sources of information concerning incidents at sea: distress signals send out by Coast Guards, news articles, reports by different partners, testimonies from migrants, satellite imagery. It inscribes these incidents within the complex political ecology of the Mediterranean: overlapping Search and Rescue zones, maritime patrols, radar coverage.

By assembling these multiple sources of information so as to document with the highest possible degree of precision incidents at sea and by spatialising this data, the aim is to develop a new tool to increase accountability in the Mediterranean.

During the three weeks of the B4P journey, the WatchTheMed platform will be regularly updated. Help us monitor the maritime borders of the EU by reporting an incident, maritime patrols or means of surveillance on the website www.watchthemed.crowdmap.com or send us an email at: obs@boats4people.org.

For more information on the Forensic Oceanography project visit:

http://www.forensic-architecture.org/investigations/forensic-oceanography/

WatchTheMed

Una piattaforma per mappare le violazioni dei diritti dei migranti ai confini marittimi dell’ EU.

WatchTheMed è una collaborazione fra Boats4People e il progetto di ricerca Forensic Oceanography del Goldsmiths College.

WatchTheMed vuole essere uno strumento per mettere fine all’impunità per la morte dei migranti in mare e la violazione dei loro diritti ai confini marittimi dell’UE. Per fare questo, monitora e mappa in tempo (quasi) reale casi di migranti in difficoltà in mare, di violazioni dei loro diritti e di decessi. Questi episodi vengono inscritti nell’ambito della complessa ecologia politica del Mediterraneo, con un attenzione particolare al Canale di Sicilia.

Questa mappa è un progetto pilota partito nel luglio 2012. Aiutaci a monitorare i confini marittimi dell’ Unione Europea, visita il sito www.watchthemed.crowdmap.com.

WatchTheMed

Une plateforme pour cartographier les violations des droits des migrants aux frontières maritimes de l’UE

WatchTheMed est une collaboration entre Boats4People et le projet de recherche Forensic Oceanography de l’Université de Goldsmiths, Londres.

WatchTheMed vise à être un outil pour mettre un terme à l’impunité qui entoure les morts des migrants et les violations de leurs droits aux frontières maritimes de l‘ UE. A cette fin, le projet observe et cartographie en temps presque réel les cas rapportés de détresse, de violations du droit et de morts en mer, et inscrit ceux-ci dans la structure complexe de la Méditerranée, en mettant l’accent sur le Canal de Sicile.

Cette carte est un projet pilote lancé en juillet 2012. Aidez nous à observer les frontières maritimes de l’UE, rapportez un incident en visitant le site www.watchthemed.crowdmap.com.

Filed under European Union, Frontex, Italy, Libya, Malta, Mediterranean, News, Reports, Tunisia

Frontex Director is Leading Candidate for Finnish Interior Ministry Position

Frontex Executive Director Ilkka Laitinen is a leading candidate for the recently vacated position of Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of the Interior in Finland. He was passed over for the position when it was last open. Prior to becoming Frontex’s Director, Laitinen was the Deputy Head of Division, Frontier Guard HQ, in Finland. Laitinen has been the Executive Director of Frontex since its inception in 2005.

Filed under European Union, Frontex, News

AI Report: S.O.S. Europe – Human Rights and Migration Control

Amnesty International today has released a report, “S.O.S. Europe: Human Rights and Migration Control,” examining “the human rights consequences for migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers that have occurred in the context of Italy’s migration agreements with Libya.”

Amnesty International today has released a report, “S.O.S. Europe: Human Rights and Migration Control,” examining “the human rights consequences for migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers that have occurred in the context of Italy’s migration agreements with Libya.”

The Report is accompanied by the “the launch of Amnesty International’s ‘When you don’t exist campaign‘, which … seeks to hold to account any European country which violates human rights in enforcing migration controls. When you don’t exist aims to defend the rights of migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers in Europe and around its borders. … Today, Europe is failing to promote and respect the rights of migrants, asylum-seekers and refugees. Hostility is widespread and mistreatment often goes unreported. As long as people on the move are invisible, they are vulnerable to abuse. Find out more at www.whenyoudontexist.eu.”

Excerpts from S.O.S. Europe Report:

“WHAT IS EXTERNALIZATION?

Over the last decade, European countries have increasingly sought to prevent people from reaching Europe by boat from Africa, and have “externalized” elements of their border and immigration control. …

European externalization measures are usually based on bilateral agreements between individual countries in Europe and Africa. Many European countries have such agreements, but the majority do not publicize the details. For example, Italy has co-operation agreements in the field of “migration and security” with Egypt, Gambia, Ghana, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal and Tunisia,2 while Spain has co-operation agreements on migration with Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali and Mauritania.3

At another level, the European Union (EU) engages directly with countries in North and West Africa on migration control, using political dialogue and a variety of mechanisms and financial instruments. For example in 2010, the European Commission agreed a cooperation agenda on migration with Libya, which was suspended when conflict erupted in 2011. Since the end of the conflict, however, dialogue between the EU and Libya on migration issues has resumed.

The European Agency for the Management of Operational Co-operation at the External Borders of the Member States of the EU (known as FRONTEX) also operates outside European territory. FRONTEX undertakes sea patrols beyond European waters in the Mediterranean Sea, and off West African coasts, including in the territorial waters of Senegal and Mauritania, where patrols are carried out in cooperation with the authorities of those countries.

The policy of externalization of border control activities has been controversial. Critics have accused the EU and some of its member states of entering into agreements or engaging in initiatives that place the rights of migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers at risk. A lack of transparency around the various agreements and activities has fuelled criticism.

This report examines some of the human rights consequences for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers that have occurred in the context of Italy’s migration agreements with Libya. It also raises concerns about serious failures in relation to rescue-at-sea operations, which require further investigation. The report is produced as part of wider work by Amnesty International to examine the human rights impacts of European externalization policies and practices.

[***]

AGREEMENTS BETWEEN ITALY AND LIBYA

[***]

The implementation of the agreements between Libya and Italy was suspended in practice during the first months of the conflict in Libya, although the agreements themselves were not set aside. While the armed conflict was still raging in Libya, Italy signed a memorandum of understanding with the Libyan National Transitional Council in which the two parties confirmed their commitment to co-operate in the area of irregular migration including through “the repatriation of immigrants in an irregular situation.”8 In spite of representations by Amnesty International and others on the current level of human rights abuses, on 3 April 2012 Italy signed another agreement with Libya to “curtail the flow of migrants”.9 The agreement has not been made public. A press release announced the agreement, but did not include any details on the measures that have been agreed, or anything to suggest that the present dire human rights predicament confronting migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers in Libya will be addressed.

[***]

HUMAN RIGHTS OBLIGATION BEYOND BORDERS

Human rights and refugee law requires all states to respect and protect the rights of people within their jurisdiction: this includes people within the state’s territorial waters, and also includes a range of different contexts where individuals may be deemed to be within a certain state’s jurisdiction.

[***]

States must also ensure that they do not enter into agreements – bilaterally or multilaterally – that would result in human rights abuses. This means states should assess all agreements to ensure that they are not based on, or likely to cause or contribute to, human rights violations. In the context of externalization, this raises serious questions about the legitimacy of European involvement – whether at a state-to-state level or through FRONTEX – in operations to intercept boats in the territorial waters of another state, when those intercepted would be at a real risk of human rights abuses.

A state cannot deploy its official resources, agents or equipment to implement actions that would constitute or lead to human rights violations, including within the territorial jurisdiction of another state.

CONCLUSION

Agreements between Italy and Libya include measures that result in serious human rights violations. Agreements between other countries in Europe and North and West Africa, and agreements and operations involving the EU and FRONTEX, also need to be examined in terms of their human rights impacts. However, with so little transparency surrounding migration control agreements and practices, scrutiny to date has been limited.

[***]

RECOMMENDATIONS

Amnesty International urges all states to protect the rights of migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers, according to international standards, This report has focused on Italy.

THE ITALIAN GOVERNMENT SHOULD:

- set aside its existing migration control agreements with Libya;

- not enter into any further agreements with Libya until the latter is able to demonstrate that it respects and protects the human rights of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants and has in place a satisfactory system for assessing and recognizing claims for international protection;

- ensure that all migration control agreements negotiated with Libya or any other countries are made public.

EUROPEAN COUNTRIES AND THE EU SHOULD:

- ensure that their migration control policies and practices do not cause, contribute to, or benefit from human rights violations;

- ensure their migration control agreements fully respect international and European human rights and refugee law, as well as the law of the sea; include adequate safeguards to protect human rights with appropriate implementation mechanisms; and be made public;

- ensure their interception operations look to the safety of people in distress in interception and rescue operations and include measures that provide access to individualized assessment procedures, including the opportunity to claim asylum;

- ensure their search-and-rescue bodies increase their capacity and co-operation in the Mediterranean Sea; publicly report on measures to reduce deaths at sea; and that Search and Rescue obligations are read and implemented in a manner that is consistent with the requirements of refugee and human rights law.”

Click here (EN), here (EN), or here (FR) for Report.

See also www.whenyoudontexist.eu

Filed under Eastern Atlantic, European Union, Frontex, Italy, Libya, Mediterranean, Reports

2012 Frontex Annual Risk Analysis

Frontex posted its 2012 Annual Risk Analysis (“ARA”) on its website on 20 April. (The 2012 ARA is also available on this link: Frontex_Annual_Risk_Analysis_2012.) The stated purpose of the ARA is “to plan the coordination of operational activities at the external borders of the EU in 2013. The ARA combines an assessment of threats and vulnerabilities at the EU external borders with an assessment of their impacts and consequences to enable the Agency to effectively balance and prioritise the allocation of resources against identified risks….”

Highlights include:

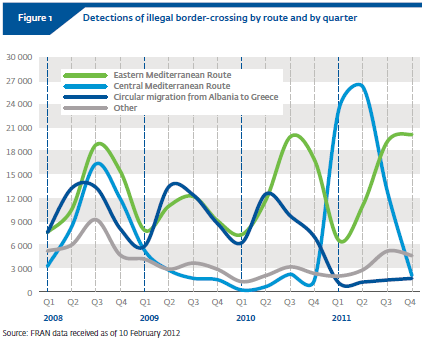

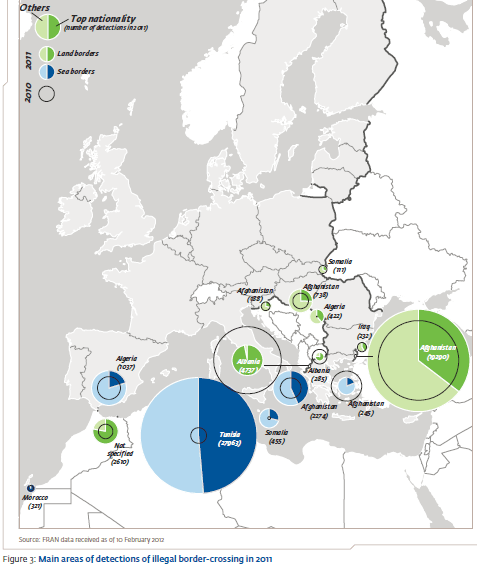

- 86% of the detections of irregular migrants in 2011 on the EU’s external borders occurred in two areas, the Central Mediterranean (46%) and the Eastern Mediterranean, primarily on the land border between Greece and Turkey (40%);

- The 64 000 detections in 2011 in the Central Mediterranean were obviously linked directly to the events in North Africa. The flow of Tunisians was reduced by 75% in the second quarter of 2011 as a result of an accelerated repatriation agreement that was signed between Italy and Tunisia;

- There is a very high likelihood of a renewed flow of irregular migrants at the southern maritime border. Larger flows, if they develop, are more likely to develop on the Central Mediterranean route because of proximity to Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt;

- Irregular migration in the Western Mediterranean towards Spain remains low, but has been steadily increasing and accounted for 6% of the EU’s detections in 2011;

- Cooperation between Spain and Mauritania, Senegal, and Mali, including bilateral agreements and the presence of patrolling assets near the African coast, are the main reasons for the decrease in arrivals on the Western African route in recent years. The situation remains critically dependent of the implementation of effective return agreements between Spain and western African countries. Should these agreements be jeopardised, irregular migration is likely to resume quickly;

- The land border between Greece and Turkey is now an established illegal-entry point for irregular migrants and facilitation networks;

- According to intelligence from JO Hermes, women embarking from North Africa to the EU are in particular danger of being intimidated by their smugglers and forced into prostitution;

- Austerity measures being implemented by Member States are likely to adversely affect operational environments of border control by reducing resources and by exacerbating corruption;

- There is an intelligence gap on terrorist groups active in the EU and their connections with irregular-migration networks. The absence of strategic knowledge may constitute a vulnerability for internal security.

Selected excerpts from the ARA:

“Executive Summary

[***] Looking ahead, the border between Greece and Turkey is very likely to remain one of the areas with the highest number of detections of illegal border-crossing along the external border. More and more migrants are expected to take advantage of Turkish visa policies and the expansion of Turkish Airlines, carrying more passengers to more destinations, to transit through Turkish air borders and subsequently attempt to enter the EU illegally. [Turkey reported an increase in 2011 of 26% in air passenger flow. See p. 12 of ARA.]

At the southern maritime borders large flows are most likely to develop on the Central Mediterranean route due to its proximity to Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, where political instability and the high unemployment rates are pushing people abroad and where there is evidence of facilitation networks also offering facilitation services to transiting migrants. [***]

There is an increasing risk of political and humanitarian crises arising in third countries which may result in the displacement of large numbers of people in search of international protection towards the land and sea borders of the EU. [***]

Various austerity measures introduced throughout Member States may result in increasing disparities between Member States in their capacity to perform border controls and hence enable facilitators to select those border types and sections that are perceived as weaker in detecting specific modi operandi. Budget cuts could also exacerbate the problem of corruption, thus increasing the vulnerability to illegal activities across the external borders. [***]

3. Situation at the external borders

[***] 3.2 Irregular migration

[***] Consistent with recent trends, the majority of detections [in 2011] were made in two hotspots of irregular migration, namely the Central Mediterranean area and the Eastern Mediterranean area accounting for 46% and 40% of the EU total, respectively, with additional effects detectable across Member States. [***]

Central Mediterranean route

[***] Initially, detections in the Central Mediterranean massively increased in early 2011, due to civil unrest erupting in the region, particularly in Tunisia, Libya and, to a lesser extent, Egypt. As a result, between January and March some 20 000 Tunisian migrants arrived on the Italian island of Lampedusa. In the second quarter of 2011 the flow of Tunisian migrants was reduced by 75% following an accelerated repatriation agreement that was signed between Italy and Tunisia. … Since October 2011, the situation has eased somewhat due to democratic elections in Tunisia and the National Transitional Council successfully gaining control of Libya. However, the situation remains of concern, with sporadic arrivals from Tunisia now adding to arrivals from Egypt. There are also some concerns that the flow from Libya may resume. [***]

Eastern Mediterranean route

[***]Undeniably, the land border between Greece and Turkey is now an established illegal-entry point for irregular migrants and facilitation networks. [***]

Western Mediterranean route (sea, Ceuta and Melilla)

Irregular migration across the Western Mediterranean towards southern Spain was at a low level through most of 2010. However, pressure has been steadily increasing throughout 2011 to reach almost 8 500 detections, or 6% of the EU total. A wide range of migrants from North African and sub-Saharan countries were increasingly detected in this region. It is difficult to analyse the exact composition of the flow, as the number of migrants of unknown nationality on this route doubled compared to the previous quarter. This may indicate an increasing proportion of nationalities that are of very similar ethnicity and/or geographic origin.

The most common and increasingly detected were migrants of unknown nationality, followed by migrants local to the region, coming from Algeria and Morocco. There were also significant increases in migrants departing from further afield, namely countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Nigeria and Congo.

In 2011, two boats were intercepted in the waters of the Balearic Islands with Algerians on board, having departed from the village of Dellys (Algeria) near Algiers. However, most migrants prefer to target the southern coast of the Iberian Peninsula.

Western African route

The cooperation between Spain and key western African countries (Mauritania, Senegal and Mali), including bilateral agreements, is developing. They are one of the main reasons for the decrease in arrivals on the Western African route over the last years, as is the presence of patrolling assets near the African coast. Despite a slight increase at the end of 2010, detections on this route remained low in 2011, almost exclusively involving Moroccan migrants.[***]

3.3.4 Trafficking in human beings

[***] According to information received from Member States, the top nationalities detected as victims of human trafficking in the EU still include Brazilians, Chinese, Nigerians, Ukrainians and Vietnamese. In addition, victims from other third countries like Albania, Ghana, Morocco, Moldova, Egypt, Indian, the Philippines and the Dominican Republic have also been reported, illustrating the broad geographical distribution of the places of origin of victims. Most THB cases are related to illegal work and sexual exploitation in Europe.

In some cases, the distinction between the smuggling of migrants and THB is not easily established because some of the migrants are initially using the services of smugglers, but it is only later, once in the EU, that they may fall victim to THB. According to intelligence from JO Hermes, this is particularly the case for women embarking for illegal border-crossing from North Africa to the EU. Once in Europe, some of them are intimated by their smugglers and forced into prostitution.

A worrying trend reported during JO Indalo is the increasing number of detections of illegal border-crossing by minors and pregnant women (see Fig. 15), as criminal groups are taking advantage of an immigration law preventing their return. Although it is not clear whether these cases are related to THB, women and children are among the most vulnerable. Most of these women claimed to be from Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire and Cameroon and were between the fifth and ninth month of pregnancy. Minors were identified as being from Nigeria, Algeria and Congo.

Another modus operandi is for the criminal groups to convince their victim to apply for international protection. Such modus operandi was illustrated by the verdict of a Dutch court case in July 2011, when one suspect was convicted for trafficking of Nigerian female minors. The asylum procedure in the Netherlands was misused by the criminal organisation to get an accommodation for the victims. The victims were forced to sexual exploitation in several Member States. [***]

5. Conclusions

[***] 1. Risk of large and sustained numbers of illegal border-crossing at the external land and sea border with Turkey

The border between Greece and Turkey is very likely to remain in 2013 among the main areas of detections of illegal border crossing along the external border, at levels similar to those reported between 2008 and 2011, i.e. between 40 000 and 57 000 detections per annum. [***]

Depending on the political situation, migrants from the Middle East may increasingly join the flow. In addition, migrants from northern and western Africa, willing to illegally cross the EU external borders, are expected to increasingly take advantage of the Turkish visa policies, granting visas to a different set of nationalities than the EU, and the expansion of Turkish Airlines, to transit through the Turkish air borders to subsequently attempt to enter the EU illegally, either by air or through the neighbouring land or sea borders. As a result, border-control authorities will increasingly be confronted with a wider variety of nationalities, and probably also a greater diversity of facilitation networks, further complicating the tasks of law-enforcement authorities.

This risk is interlinked with the risk of criminal groups facilitating secondary movements and the risk of border-control authorities faced with large flows of people in search of international protection. [***]

3. Risk of renewed large numbers of illegal border-crossing at the southern maritime border

The likelihood of large numbers of illegal border-crossing in the southern maritime border remains very high, either in the form of sporadic episodes similar to those reported in 2011 or in sustained flows on specific routes originating from Africa.

Irregular-migration flows at the southern maritime borders are expected to be concentrated within one of the three known routes, i.e. the Central Mediterranean route, the Western Mediterranean route or the Western African route. Larger flows are more likely to develop on the Central Mediterranean route than on the other two routes, because of its proximity to Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, where political instability and high unemployment rate among young people is pushing people away from their countries and where there is evidence for well-organised facilitation networks.

On the Western Mediterranean route, the situation remains of concern because of the increasing trend of illegal border-crossing reported throughout 2011. According to reported detections, the situation on the Western African route has been mostly under control since 2008 but remains critically dependant of the implementation of effective return agreements between Spain and western African countries. Should these agreements be jeopardised, irregular migration pushed by high unemployment and poverty is likely to resume quickly despite increased surveillance.

The composition of the flow is dependent on the route and the countries of departure, but includes a large majority of western and North Africans. Mostly economically driven, irregular migration on these routes is also increasingly dependent on the humanitarian crisis in western and northern African countries. Facilitators are increasingly recruiting their candidates for illegal border-crossing from the group that are most vulnerable to THB, i.e. women and children, causing increasing challenges for border control authorities.

4. Risk of border-control authorities faced with large numbers of people in search of international protection

Given the currently volatile and unstable security situation in the vicinity of the EU, there is an increasing risk of political and humanitarian crises in third countries resulting in large numbers of people in search of international protection being displaced to the land and sea borders of the EU. The most likely pressures are linked to the situation in North Africa and the Middle East. In addition, the situation in western African countries like Nigeria may also trigger flows of people in search of international protection at the external borders. [***]

6. Risk of less effective border control due to changing operational environment

At the horizon of 2013, the operational environments of border control are likely to be affected, on the one hand, by austerity measures reducing resources, and on the other hand, by increased passenger flows triggering more reliance on technological equipment.

Austerity measures have been introduced throughout Member States in various forms since 2009. The most obvious examples are found in Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and the Baltic countries. These measures could result in increasing disparities between Member States in their capacity to perform border controls and hence enabling facilitators to select border types and sections that are perceived as weaker in detecting specific modi operandi.

Budget cuts could also exacerbate the problem of corruption, increasing the vulnerability to illegal activities across the external borders.

Austerity measures will inevitably impact on the efficacy of border-control authorities in detecting and preventing a wide array of illegal activities at the borders, ranging from illegal border-crossing through smuggling of excise goods to THB. [***]

8. Risk of border-control authorities increasingly confronted with cross-border crimes and travellers with the intent to commit crime or terrorism within the EU

[***]There is an intelligence gap on terrorist groups that are active in the EU and their connections with irregular-migration networks. The absence of strategic knowledge on this issue at the EU level may constitute a vulnerability for internal security. Knowledge gained at the external borders can be shared with other law enforcement authorities to contribute narrowing this gap.”

Click here or on this link: Frontex_Annual_Risk_Analysis_2012, for 2012 Frontex ARA.

Click here for Frontex press statement on the 2012 ARA.

Click here for my post on the 2011 ARA.

Filed under Aegean Sea, Analysis, Data / Stats, Eastern Atlantic, European Union, Frontex, Mediterranean, News, Reports

EU Court of Justice Advocate General Recommends Annulment of Frontex Sea Borders Rule

ECJ Advocate General Paolo Mengozzi issued an Opinion on 17 April in which he recommended that the European Court of Justice annul Council Decision 2010/252/EU of 26 April 2010 supplementing the Schengen Borders Code as regards the surveillance of the sea external borders in the context of operational cooperation coordinated by Frontex (Sea Borders Rule). The Advocate General’s recommendation, issued in the case of the European Parliament v Council of the EU, Case C-355/10, will be considered by the ECJ in the coming weeks. The case was filed by the European Parliament on 12 July 2010. A hearing was conducted on 25 January 2012.

The Advocate General’s recommendation is based primarily on the conclusion that the Council adopted the Frontex Sea Borders Rule by invoking a procedure which may only be used to amend “non-essential elements” of the Schengen Borders Code. The Advocate General concluded that rather than amending “non-essential elements” of the SBC, the Council Decision introduces “new essential elements” into the SBC and amends the Frontex Regulation. The recommendation calls for the effects of the Sea Borders Rule to be maintained until a new act can be adopted in accordance with ordinary legislative procedures.

[UPDATE:] Paragraph 64 of the Recommendation explains why the Commission likely sought to implement the Sea Borders Rule through the committee mechanism rather than by pursuing ordinary legislative procedures:

“64. Firstly, some provisions of the contested decision concern problems that, as well as being sensitive, are also particularly controversial, such as, for example, the applicability of the principle of non-refoulement in international waters (51) or the determination of the place to which rescued persons are to be escorted under the arrangements introduced by the SAR Convention. (52) The Member States have different opinions on these problems, as is evident from the proposal for a decision submitted by the Commission. (Ftnt 53)

Ftnt 53 – Moreover, it would seem that it is precisely a difference of opinion and the impasse created by it which led to the Commission’s choosing to act through the committee mechanism under Article 12(5) of the SBC rather than the ordinary legislative procedure, as is clear also from the letter from Commissioner Malmström annexed to the reply. These differences persist. The provisions of the contested decision concerning search and rescue, for example, have not been applied in Frontex operations launched after the entry into force of the contested decision on account of opposition from Malta.”

While this case presents a procedural question and does not involve a review of any of the substantive provisions of the Sea Borders Rule, the Advocate General’s statement in Paragraph 64 that “the applicability of the principle of non-refoulement in international waters” is a “controversial” position is wrong. Perhaps the position is still controversial in some circles, but legally, with the important exception expressed by the US Supreme Court, it is clear that non-refoulement obligations apply to actions taken in international waters.

Click here for Opinion of Advocate General Mengozzi, Case C-355/10, 17 April 2012.

Click here, here, and here for articles.

Click here for my last post on the case.

Extensive Excerpts from the Advocate General’s Recommendation:

“1. In the present proceedings, the European Parliament requests the Court to annul Council Decision 2010/252/EU of 26 April 2010 supplementing the Schengen Borders Code (2) as regards the surveillance of the sea external borders in the context of operational cooperation coordinated by the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union (‘the contested decision’). (3) If the action should be upheld, Parliament requests that the effects of the contested decision be maintained until it shall have been replaced.

[***]

9. The contested decision was adopted on the basis of Article 12(5) of the SBC, in accordance with the procedure provided for in Article 5a(4) of the comitology decision … [***]

10. According to recitals (2) and (11) of the contested decision, its principal objective is the adoption of additional rules for the surveillance of the sea borders by border guards operating under the coordination of the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union (‘the Agency’ or ‘Frontex’), established by Regulation 2007/2004 (‘the Frontex Regulation’). (9) It consists of two articles and an annex divided into two parts entitled ‘Rules for sea border operations coordinated by the Agency’ and ‘Guidelines for search and rescue situations and for disembarkation in the context of sea border operations coordinated by the Agency’. Under Article 1, ‘[t]he surveillance of the sea external borders in the context of the operational cooperation between Member States coordinated by the … Agency … shall be governed by the rules laid down in Part I to the Annex. Those rules and the non-binding guidelines laid down in Part II to the Annex shall form part of the operational plan drawn up for each operation coordinated by the Agency.’

11. Point 1 of Part I to the Annex lays down certain general principles intended, inter alia, to guarantee that maritime surveillance operations are conducted in accordance with fundamental rights and the principle of non-refoulement. Point 2 contains detailed provisions on interception and lists the measures that may be taken in the course of the surveillance operation ‘against ships or other sea craft with regard to which there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that they carry persons intending to circumvent the checks at border crossing points’ (point 2.4). The conditions for taking such measures vary depending on whether the interception takes place in the territorial waters and contiguous zone of a Member State (point 2.5.1) or on the high seas (point 2.5.2). Point 1 of Part II to the Annex lays down provisions on units participating in the surveillance operation in search and rescue situations, including with regard to communicating and forwarding information to the rescue coordination centre responsible for the area in question and the coordination centre of the operation, and defines certain conditions for the existence of an emergency (point 1.4). Point 2 lays down guidelines on the modalities for the disembarkation of the persons intercepted or rescued.

II – Procedure before the Court and forms of order sought

12. By act lodged at the Registry of the Court of Justice on 12 July 2010, the Parliament brought the action which forms the subject-matter of the present proceedings. The Commission intervened in support of the Council. At the hearing of 25 January 2012, the agents of the three institutions presented oral argument.

13. The Parliament claims that the Court should annul the contested decision, rule that the effects thereof be maintained until it is replaced, and order the Council to pay the costs.

14. The Council contends that the Court should dismiss the application as inadmissible or, in the alternative, as unfounded and order the Parliament to pay the costs.

15. The Commission requests the Court to dismiss the application and order the Parliament to pay the costs.

III – Application

A – Admissibility

[***]

23. For all the reasons set out above, the application must, in my view, be declared admissible.

B – Substance

24. The Parliament considers that the contested decision exceeds the implementing powers conferred by Article 12(5) of the SBC and therefore falls outside the ambit of its legal basis. In that context it raises three complaints. Firstly, the contested decision introduces new essential elements into the SBC. Secondly, it alters essential elements of the SBC. Thirdly, it interferes with the system created by the Frontex Regulation. These complaints are examined separately below.

[***]

3. First complaint, alleging that the contested decision introduces new essential elements into the SBC

[***]

61. Given both the sphere of which the legislation in question forms part and the objectives and general scheme of the SBC, in which surveillance is a fundamental component of border control policy, and notwithstanding the latitude left to the Commission by Article 12(5), I consider that strong measures such as those listed in point 2.4 of the annex to the contested decision, in particular those in subparagraphs (b), (d), (f) and g), and the provisions on disembarkation contained in Part II to that annex, govern essential elements of external maritime border surveillance. These measures entail options likely to affect individuals’ personal freedoms and fundamental rights (for example, searches, apprehension, seizure of the vessel, etc.), the opportunity those individuals have of relying on and obtaining in the Union the protection they may be entitled to enjoy under international law (this is true of the rules on disembarkation in the absence of precise indications on how the authorities are to take account of the individual situation of those on board the intercepted vessel), (47) and also the relations between the Union or the Member States participating in the surveillance operation and the third countries involved in that operation.

62. In my view, a similar approach is necessary with regard to the provisions of the contested decision governing interception of vessels on the high seas. On the one hand, those provisions expressly authorise the adoption of the measures mentioned in the preceding paragraph in international waters, an option which, in the context described above, is essential in nature, irrespective of whether or not the Parliament’s argument is well founded, that the geographical scope of the SBC, with regard to maritime borders, is restricted to the external limit of the Member State’s territorial waters or the contiguous zone, and does not extend to the high seas. (48) On the other hand, those provisions, intended to ensure the uniform application of relevant international law in the context of maritime border surveillance operations, (49) even if they do not create obligations for the Member States participating in those operations or confer powers on them, other than those that may be deduced from that legislation, do bind them to a particular interpretation of those obligations and powers, thereby potentially bringing their international responsibility into play. (50)

63. Two further observations militate in favour of the conclusions reached above.

64. Firstly, some provisions of the contested decision concern problems that, as well as being sensitive, are also particularly controversial, such as, for example, the applicability of the principle of non-refoulement in international waters (51) or the determination of the place to which rescued persons are to be escorted under the arrangements introduced by the SAR Convention. (52) The Member States have different opinions on these problems, as is evident from the proposal for a decision submitted by the Commission. (53)

65. Secondly, a comparison with the rules on border checks contained in the SBC shows that the definition of the practical arrangements for carrying out those checks, in so far as they concern aspects comparable, mutatis mutandis, to those governed by the contested decision, was reserved to the legislature, and this is so notwithstanding the fact that the Commission expressed a different opinion in the proposal for a regulation. (54)

66. In the light of all the preceding provisions, I consider that the contested decision governs essential elements of the basic legislation within the meaning of the case-law set out in points 26 to 29 of this Opinion.

67. Therefore, the Parliament’s first complaint must, in my opinion, be upheld.

4. Second complaint, alleging that the contested decision alters essential elements of the SBC

68. In its second complaint, the Parliament claims that, by providing that border guards may order the intercepted vessel to change its course towards a destination outside territorial waters and conduct it or the persons on board to a third country [point 2.4(e) and (f) of Part I to the annex], the contested decision alters an essential element of the SBC, that is to say, the principle set out in Article 13, under which ‘[e]ntry may only be refused by a substantiated decision stating the precise reasons for the refusal.’

69. The Parliament’s argument is based on the premise that Article 13 is applicable to border surveillance too. This interpretation is opposed by both the Council and the Commission, which consider that the obligation to adopt a measure for which reasons are stated pursuant to that provision exists only when a person who has duly presented himself at a border crossing point and been subject to the checks provided for in the SBC has been refused entry into the territory of Union.

70. The Parliament’s complaint must, in my view, be rejected, with no need to give a ruling, as to the substance, on the delicate question of the scope of Article 13 SBC on which the Court will, in all likelihood, be called to rule in the future.

[***]

5. Third complaint, alleging that the contested decision amends the Frontex Regulation

[***]

82. However, the fact remains that Article 1 of the contested decision substantially reduces the latitude of the requesting Member State and, consequently, that of the Agency, potentially interfering significantly with its functioning. An example of this is provided by the events connected with the Frontex intervention requested by Malta in March 2011 in the context of the Libyan crisis. The request by Malta, inter alia, not to integrate into the operational plan the guidelines contained in Part II to the annex to the contested decision met with opposition from various Member States and involved long negotiations between the Agency and the Maltese Government which prevented the operation from being launched. (62)

83. In actual fact, the annex to the contested decision as a whole, including the non-binding guidelines – whose mandatory force, given the wording of Article 1, it is difficult to contest – (63) is perceived as forming part of the Community measures relating to management of external borders whose application the Agency is required to facilitate and render more effective under Article 1(2) of the Frontex Regulation. (64)

84. Furthermore, the non-binding guidelines contained in Part II to the annex to the contested decision relating to search and rescue situations govern aspects of the operation that do not fall within Frontex’s duties. As the Commission itself points out in the proposal on the basis of which the contested decision was adopted, Frontex is not an SAR agency (65) and ‘the fact that most of the maritime operations coordinated by it turn into search and rescue operations removes them from the scope of Frontex’. (66) The same is true with regard to the rules on disembarkation. None the less, the contested decision provides for those guidelines to be incorporated into the operational plan.

85. On the basis of the foregoing considerations, I consider that, by regulating aspects relating to operational cooperation between Member States in the field of management of the Union’s external borders that fall within the scope of the Frontex Regulation and, in any event, by laying down rules that interfere with the functioning of the Agency established by that regulation, the contested decision exceeds the implementing powers conferred by Article 12(5) of the SBC.

[***]

C – Conclusions reached on the application

89. In the light of the foregoing, the action must, in my view, be allowed and the contested decision annulled.

IV – Parliament’s request that the effects of the contested decision be maintained

90. The Parliament requests the Court, should it order the annulment of the contested decision, to maintain the effects thereof until a new act be adopted, pursuant to the power conferred on it by the second paragraph of Article 264 TFEU. That provision, under which ‘the Court shall, if it considers this necessary, state which of the effects of the act which it has declared void shall be considered as definitive’ has also been used to maintain temporarily all the effects of such an act pending its replacement. (68)

91. In the present case, annulment pure and simple of the contested decision would deprive the Union of an important legal instrument for coordinating joint action by the Member States in the field of managing surveillance of the Union’s maritime borders, and for making that surveillance more in keeping with human rights and the rules for the protection of refugees.

92. For the reasons set out, I consider that the Parliament’s application should be granted and the effects of the contested decision maintained until an act adopted in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure shall have been adopted.

[***]”

Click here for Opinion of Advocate General Mengozzi, Case C-355/10, 17 April 2012.

Click here, here, and here for articles.

Click here for previous post on topic.

Filed under European Union, Frontex, Judicial, News

PACE Report on “Lives Lost in the Mediterranean Sea: Who is Responsible?” Scheduled for Release on 29 March

The draft report prepared by Tineke Strik (Netherlands, SOC), “Lives lost in the Mediterranean Sea: who is responsible?”, will be considered on 29 March in a closed session by the PACE Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced Persons.