In January of this year, the Frontex Risk Analysis Unit (RAU) released its 2012 Third Quarter Report (July – September 2012). (Frontex has since released Reports for Q4 2012 and Q1 2013; we will post summaries of these more recent Reports shortly.) As in past quarters, the 70-page report provided in-depth information about irregular migration patterns at the EU external borders. The report is based on data provided by 30 Member State border-control authorities, and presents results of statistical analysis of quarterly variations in eight irregular migration indicators and one asylum indicator.

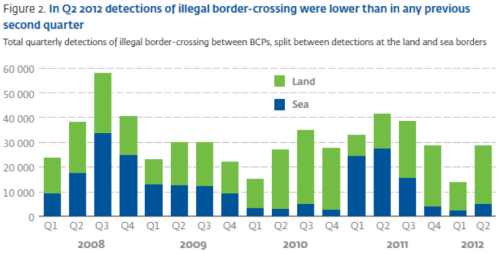

During 2012 Q3 several FRAN indicators varied dramatically compared with previous reports, including a significant reduction in detections of illegal border-crossing compared with previous third quarters. In fact, there were fewer detections of illegal border-crossing than in any third quarter since data collection began in early 2008. Additionally, this quarter reported the largest number of applications for asylum since data collection began in early 2008, with Syrians ranking first among nationalities.

During 2012 Q3 several FRAN indicators varied dramatically compared with previous reports, including a significant reduction in detections of illegal border-crossing compared with previous third quarters. In fact, there were fewer detections of illegal border-crossing than in any third quarter since data collection began in early 2008. Additionally, this quarter reported the largest number of applications for asylum since data collection began in early 2008, with Syrians ranking first among nationalities.

Here are some highlights from the Report focusing on the sea borders:

- “There were 22,093 detections of illegal border-crossing at the EU level, which is considerably lower than expected based on previous reporting periods.”

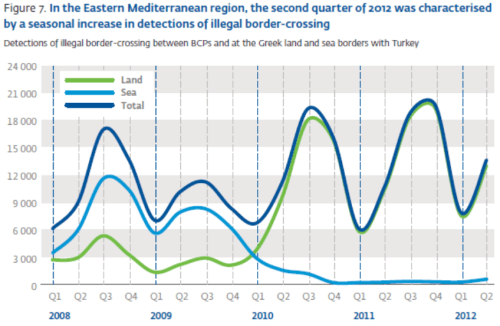

- “The majority of detections were at the EU external land (66%), rather than sea border, but this was the lowest proportion for some time due to an increase in detections at the Greek sea border with Turkey [***]. Nevertheless, the Greek land border with Turkey was still by far the undisputed hotspot for detections of illegal border-crossing.”

- “Overall, in Q3 2012 there were fewer detections of illegal border-crossing than in any previous third quarter, following the launch of two Greek Operations: Aspida (Shield) … and Xenios Zeus…. Perhaps somewhat predictably, there were increased detections of illegal border-crossing at both the Turkish sea border with Greece and land border with Bulgaria, indicative of weak displacement effects from the operational area.”

- “[T]here were more than 3 500 reported detections of illegal border-crossing on the main Central Mediterranean route (Italian Pelagic Islands, Sicily and Malta), a significant decrease compared to the same reporting period in 2011 during the peak associated with the Arab Spring, but still the highest reported so far in 2012, and higher than the pre-Arab Spring peak of 2010.”

- “[D]etections in Italy still constituted more than a fifth of all detections at the EU level. Detections in Apulia and Sicily were actually higher than in the Arab Spring period, and doubled in Lampedusa compared to the previous quarter.”

- “In July 2012 the facilitation networks targeted Sicily instead of Pantelleria and Lampedusa, as it is harder for the migrants to reach the Italian mainland from the small islands. Migrants claim that the facilitators may start to focus on the southern coast of Sicily, as they expect lower surveillance there.”

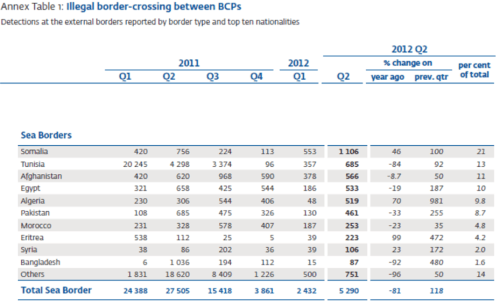

- “[T]here were some significant increases of various nationalities such as Tunisians and Egyptians departing from their own countries, and Somalis and Eritreans departing from Libya.”

- “Several reports included details of how sub-Saharan migrants were often deceived, over-charged or even left to drown by their facilitators during the embarkation process.”

- “For some time there has been a steady flow of Afghans and, to a lesser extent, Pakistanis arriving in the southern Italian blue borders of Calabria and Apulia with some very large increases observed during Q3 2012. In fact, according to the FRAN data there were more detections in this region than ever before.”

- “JO EPN Aeneas 2012 started on 2 July. The operational plan defines two operational areas, Apulia and Calabria, covering the seashore along the Ionian Sea and part of the Adriatic Sea.”

- “JO EPN Indalo 2012 started in [the Western Mediterranean] on 16 May covering five zones of the south-eastern Spanish sea border and extending into the Western Mediterranean.”

- “Increased border surveillance along the Mauritanian coast generated by the deployment of joint Mauritanian-Spanish police teams and also joint maritime and aerial patrols in Mauritanian national waters has reduced departures towards the Canary Islands but also may have resulted in a displacement effect to the Western Mediterranean route from the Moroccan coast.”

- “The good cooperation among the Spanish, Senegalese and Mauritanian authorities and the joint patrols in the operational sea areas and on the coastline of Senegal and Mauritania have resulted in a displacement of the departure areas of migrant boats towards the Canary Islands, with the reactivation of the Western African route (from north of Mauritania to the Western Sahara territory) used by the criminal networks operating in Mauritania.”

Here are excerpts from the Report focusing on the sea borders:

“Overall, in Q3 2012 there were fewer detections of illegal border-crossing than in any previous third quarter, following the launch of two Greek Operations: Aspida (Shield), which involved the deployment of ~1 800 Greek police officers to the Greek land border with Turkey, and Xenios Zeus, which focused on the inland apprehension of illegally staying persons. The much-increased surveillance and patrolling activities at the Greek-Turkish land border, combined with the lengthening of the detention period to up to 6 months, resulted in a drastic drop in the number of detections of irregular migrants from ~2 000 during the first week of August to below ten per week in each of the last few weeks of October. Perhaps somewhat predictably, there were increased detections of illegal border-crossing at both the Turkish sea border with Greece and land border with Bulgaria, indicative of weak displacement effects from the operational area….

Despite the clear impact of the Greek operational activities on the number of detections of illegal border-crossing, there is little evidence to suggest that the absolute flow of irregular migrants arriving in the region has decreased in any way. In fact, document fraud on flights from Istanbul increased once the Greek operations commenced. Hence, there remains a very significant risk of a sudden influx of migrants immediately subsequent to the end of the operations.”

[***]

4.1 Detections of Illegal border-crossing

“Overall, in Q3 2012 there were 22 093 detections of illegal border-crossing at the EU level, which is considerably lower than expected based on detections during previous quarters. In fact, there were fewer detections of illegal border-crossing than in any third quarter since data collection began in early 2008. The particularly low number of detections was due to vastly increased operational activity at the Greek land border with Turkey since 30 July 2012, and also to the overlapping effects of the end of the Arab Spring in its initial countries (Egypt, Libya, Tunisia) and far fewer detections of circular Albanian migrants illegally crossing the border into Greece.

The majority of detections were at the EU external land (66%), rather than sea border, but this was the lowest proportion for some time due to an increase in detections at the Greek sea border with Turkey – probably the result of a weak displacement effect from the land border. Nevertheless, the Greek land border with Turkey was still by far the undisputed hotspot for detections of illegal border-crossing.”

“Figure 4 shows the evolution of the FRAN Indicator 1A – detections of illegal border- crossing, and the proportion of detections between the land and sea borders of the EU per quarter since the beginning of 2008. The third quarter of each year is usually influenced by weather conditions favourable for both approaching and illegally crossing the external border of the EU. Moreover, good conditions for illegal border-crossing also make it easier to detect such attempts. The combination of these two effects means that the third quarter of each year is usually the one with very high, and often the highest number of detections.”

“Figure 4 shows the evolution of the FRAN Indicator 1A – detections of illegal border- crossing, and the proportion of detections between the land and sea borders of the EU per quarter since the beginning of 2008. The third quarter of each year is usually influenced by weather conditions favourable for both approaching and illegally crossing the external border of the EU. Moreover, good conditions for illegal border-crossing also make it easier to detect such attempts. The combination of these two effects means that the third quarter of each year is usually the one with very high, and often the highest number of detections.”

[***]

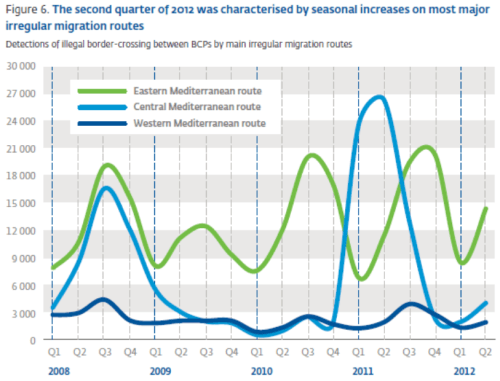

4.2 Routes

“… As illustrated in Figure 8, in the third quarter of 2012 the most detections of illegal border-crossings were reported on the Eastern and Central Mediterranean routes, which is consistent with the overall trend for most third quarters in the past. However, on the Eastern Mediterranean route the summer peak of detections, which has been remarkably consistent over recent years, was much lower than expected following increased operational activity in the area resulting in far fewer detections during the final month of the quarter.

In the Central Mediterranean, increased detections of several nationalities illegally crossing the blue border to Lampedusa and Malta, as well as increased landings in Apulia and Calabria from Greece and Turkey, combined to produce the highest number of detections both before and after the prominent peak reported during the Arab Spring in 2011.

In Q3 2012, there were 11 072 detections of illegal border-crossing on the Eastern Mediterranean route, a 75% reduction compared to the same period in 2011, and most other third quarters (Fig. 8). Nevertheless this route was still the undisputed hotspot for illegal entries to the EU during the current reporting period, mostly because of vastly increased detections of Syrian nationals.”

4.2.1 Eastern Mediterranean Route

“…Italian Ionian coast: For some time there has been a steady flow of Afghans and, to a lesser extent, Pakistanis arriving in the southern Italian blue borders of Calabria and Apulia with some very large increases observed during

Q3 2012. In fact, according to the FRAN data there were more detections in this region than ever before. The most commonly detected migrants were from Afghanistan, which is a significant but steady trend. In contrast detections of migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Syria have increased very sharply since the beginning of 2012.

JO EPN Aeneas 2012 started on 2 July. The operational plan defines two operational areas, Apulia and Calabria, covering the seashore along the Ionian Sea and part of the Adriatic Sea. As mentioned in previous FRAN Quarterlies,

the detections at the Greek-Turkish land border are directly correlated with detections in the Ionian Sea. In 2011, it was estimated that more than 15% of migrants reported at the Greek-Turkish land border were afterwards detected in Apulia and Calabria.”

[***]

4.2.2 Central Mediterranean Route

“… According to FRAN data, in Q3 2012 there were just 3 427 reported detections of illegal border-crossing on the main Central Mediterranean route (Italian Pelagic Islands, Sicily and Malta), a significant decrease compared to the same reporting period in 2011. However, this figure was still the highest reported so far in 2012, and was higher than the peak in 2010. Additionally, there were some significant increases in various nationalities.

On the Central Mediterranean route, detections of migrants from Tunisia continued to in crease from 82 during the last quarter of 2011 to over 1 000 in Q3 2012. Tunisians were not the only North African nationality to feature in the top five most detected nationalities in the Central Mediterranean region, as Egyptians were also detected in significant and increasing numbers (287). The fact that fewer Egyptians than Tunisians were detected in the Central Mediterranean should be interpreted in light of Egypt being eight times more populous than Tunisia, which shows that irregular migration pressure from Egypt is proportionally much lower than that from Tunisia.

Also significant in the Central Mediterranean during the third quarter of 2012 were detections of Somalis (854) and, following recent increases, also Eritreans (411). Somalis have been detected in similarly high numbers during previous reporting periods (for example over 1 000 in Q2 2012) but there were more Eritreans detected in Q3 2012 than ever before.

Some Syrian nationals were also detected using the direct sea route from Turkey to Italy but these tended to arrive in Calabria…..”

[***]

4.2.3 Western Mediterranean Route

“In 2011, irregular migration in the Western Mediterranean region increased steadily from just 890 detections in Q1 2011 to 3 568 detections in the third quarter of the year. A year later in Q3 2012, detections dropped to just over 2 000 detections, which was, nevertheless, the highest level so far in 2012.

As has been the case for several years, most of the detections involved Algerians (859) followed by migrants of unknown nationality (524, presumed to be sub-Saharan Africans). Algerians were mostly detected in Almeria

and at the land border with Morocco, the migrants of unknown nationality were mostly reported from the land borders.

JO EPN Indalo 2012 started in this region on 16 May covering five zones of the south-eastern

Spanish sea border and extending into the Western Mediterranean.

In Q3 2012, there were far fewer Moroccan nationals detected (79) compared to Q3 2011. Most were detected just east of the Gibraltar Strait, between Tangiers and Ceuta. According to the migrants’ statements, the area between Ksar Sghir and Sidi Kankouche is the most popular departing area among Moroccans who want to cross the Gibraltar strait (10.15 NM distance). The boats used for the sea crossing were toy boats bought by the migrants in a supermarket for EUR ~100….

Increased border surveillance along the Mauritanian coast generated by the deployment of joint Mauritanian-Spanish police teams and also joint maritime and aerial patrols in Mauritanian national waters has reduced departures towards the Canary Islands but also may have resulted in a displacement effect to the Western Mediterranean route from the Moroccan coast.”

[***]

4.2.4 Western African Route

“In the third quarter of 2012, there were just 40 detections of illegal border-crossing in this region, almost exclusively of Moroccan nationals but with an influx of Senegalese nationals….

The good cooperation among the Spanish, Senegalese and Mauritanian authorities and the joint patrols in the operational sea areas and on the coastline of Senegal and Mauritania have resulted in a displacement of the

departure areas of migrant boats towards the Canary Islands, with the reactivation of the Western African route (from north of Mauritania to the Western Sahara territory) used by the criminal networks operating in Mauritania.”

[***]

——————-

Click here or here here for Frontex FRAN Report for Q3 2012.

Click here for previous post summarizing Frontex FRAN Report for Q2 2012.